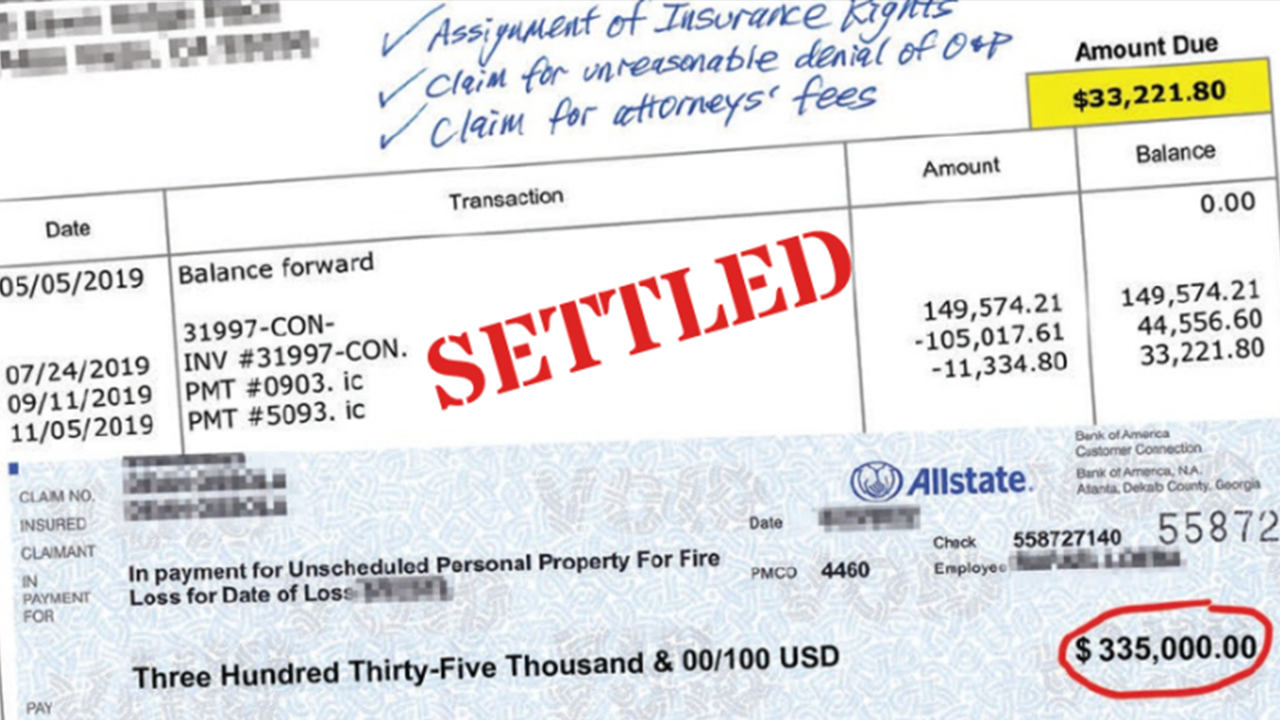

Allstate Pays Contractor $335,000 to Settle Dispute Over $33,000 Restoration Invoice – C&R

- Contractor with a long history of collecting overhead and profit for mitigation and contents is denied 10 & 10 for subcontracted contents work.

- Allstate adjuster writes: “Allstate does not cover OH&P for mitigation or contents work so unfortunately your request for OH&P for any contents work or packing will not be approved.”

- Contractor uses Assignment of Insurance Rights to sue the carrier directly for overhead, profit, and attorneys’ fees.

- Retired Allstate Property Claim Manager testifies that Allstate acted in bad faith for refusing to pay overhead and profit for contents.

SANTA ANA, CA – Allstate Insurance Company has paid $335,000 to settle an insurance bad faith lawsuit filed by an Orange County, California property damage restoration contractor with an Assignment of Insurance Rights (AOR) that included an assignment of benefits.

The case arose from a $250,000 insurance claim for a fire that burned part of the garage of a home insured by Allstate in the upscale community of Aliso Viejo, California. The homeowner engaged the services of a restoration contractor with a general contractor’s license to remediate and repair the damage to the real and personal property. The contractor was not part of a network and no TPA was involved in the claim. The contractor reported to Allstate that smoke contaminated the interior of the home and its contents. Allstate paid approximately $100,000 for mitigation and structural repairs.

The two-story, 4,000 square foot, six-bedroom home was occupied by a husband, a wife, and their children. It was heavily loaded with contents. The contents of the entire home were packed out to facilitate the carpet replacement, restoration of the floors, and painting of the walls and ceilings. Allstate agreed to the packout.

To expedite the processing of the contents, the contractor notified Allstate that it subcontracted the packout and contents restoration work to a specialty vendor. The contractor billed $149,574.21 for the contents portion of the project, which included a markup of $24,929.14 for overhead and profit.

The contents adjuster responded: “Remove O&P. O&P is not warranted for contents. It doesn’t require a high level of coordination.” It was notable that the statement did not say that this particular contents project did not require a high level of coordination. The contractor interpreted it as a universal statement that contents restoration never requires a high level of coordination, which is false. The contractor was frustrated because Allstate did not inquire with the contractor about its coordination efforts.

“Remove O&P” is an instruction. The Restoration Industry Association published a Position Statement entitled Adjusters Dictating Restoration Charges. It is a valuable tool to help restorers make the case that for work that is not performed under a managed repair program, adjusters cannot dictate restoration charges. The Statement says the adjuster “must not instruct or require restoration contractors to remove items from their invoices.” In the Aliso Viejo case, the contractor (which was assigned rights to the claim) took the position that it was bad faith for Allstate to universally declare that contents restoration does not require a high level of coordination without actually investigating the contractor’s coordination efforts for this particular project.

Carrier’s Duty to Pay O&P

Insurance companies are required to pay a reasonable cost to repair damage that occurs in covered losses. They are required to pay overhead and profit if those charges are reasonable. “Reasonable” is broadly defined in dictionaries as “fair and sensible.” The reasonable price is not necessarily the price set forth in a generic price guide. Restorers are not required to match each other’s prices; in fact, it is illegal.

Every claim is different, and every residence is different. Some restoration billing models include overhead and profit and some do not. Restorers may be able to collect overhead and profit for certain types of work even if others in their market do not charge for it. The question here was not “what is the lowest price in town?” The question was whether it was fair and sensible to charge for overhead and profit based on the unique circumstances of the project.

On non-program jobs, insurance companies are not allowed to set the prices, or dictate billing models, including the determination of whether overhead and profit is owed. The reasonable cost and billing model is that which is fair and sensible in the marketplace based on what willing buyers pay willing sellers in a competitive marketplace. Insurance companies are third parties to restoration contracts and must not interfere with those contracts. Interference may subject them to liability for damages. The insurance industry must adapt to the way the restoration industry charges for its work. It’s not the other way around.

In 2022, a claims manager for American Reliable Insurance Company testified that “the rule” is that overhead and profit is paid to a general contractor when three or more trades are involved. That approach is imperfect, but it is predictable.

Most insurance companies have moved away from counting trades and instead, they focus on complexity and “high levels” of coordination. Concepts like “complexity” and “high levels” are subjective and difficult to define. They lead to considerable confusion and conflict, to the ultimate detriment of the policyholder.

The purpose of this article is not to promote any particular billing model. To comply with antitrust laws, restoration companies must not coordinate pricing or billing models with their competitors.

Bad Faith Denial Alleged

Allstate refused to pay $8,292.66 in various charges for the contents restoration and refused to pay the $24,929.14 charged for overhead and profit, leaving an unpaid balance of $33,321.80. Several adjusters worked on the claim. Adjuster 1 wrote “Allstate does not cover OH&P for mitigation or contents.” However, the Policy contains no such language. Like most states, California’s Fair Claims Settlement Practices Regulations state: “No insurer shall misrepresent or conceal benefits [or] coverages.”[1]

The allegation that Allstate “does not cover” overhead and profit for mitigation or contents was not accurate. In fact, Allstate paid overhead and profit for mitigation on this claim. The contractor responded to the allegation with a list of 15 Allstate claims for which the contractor believed that Allstate had, in fact, paid the contractor overhead and profit for contents work. Allstate agreed that it paid overhead and profit for contents on 11 of those 15 claims, but still refused to pay any portion of the remaining balance of $33,321.80.

The Allstate Policy included personal property coverage for “sudden and accidental direct physical loss to property…caused by…smoke.” The Policy contained no explicit exclusion for “overhead and profit,” nor has the author of this article ever seen a policy that contains such an exclusion.

The laws of every state require insurance companies to handle claims promptly, fairly, and in good faith. Insurance companies face liability exposure when and if they apply blanket rules to restoration charges that should be individually investigated, including overhead and profit. Nearly every state allows policyholders or a contractor holding a properly-drafted assignment of the policyholder’s legal rights under the policy may prosecute a legal claim against an insurer for bad faith if the insurer has violated the terms of the policy and breached the duty of good faith.

The overhead and profit issue with Allstate was not isolated to the Aliso Viejo claim. Adjuster 2 on the Aliso Viejo claim wrote the following in regard to another claim that was underway while the Aliso Viejo claim was pending:

“As stated on all claims previously- remove overhead and profit. This is my third claim with you this week where I have had to ask you to remove overhead and profit for a packout/testing invoice. Please note moving forward on Allstate claims not to include this or they will be rejected.” (Emphasis added.)

Adjuster 3 wrote that he “had to remove O&P because O&P is not warranted on a pack out and clean. This does not require a high level of coordination.” The contractor interpreted these as blanket statements, rather than decisions made about this individual claim. At this point, it appeared to the contractor that Allstate was intending to implement an institutional practice to reject all claims for overhead and profit for contents restoration.

The contractor engaged the Law Offices of Edward H. Cross, which sent a settlement demand to Allstate, with a copy of the Assignment of Insurance Rights. The demand explained that the contractor stepped into the shoes of the policyholder by virtue of the Assignment. The demand explained how a restoration contractor with a properly-drafted assignment of insurance rights can prosecute a civil claim for insurance bad faith against a customer’s insurance carrier and collect attorneys’ fees and interest on the unpaid balance. The contractor did not want a lawsuit. He just wanted to get paid, so the demand included a compromise to forgo collection of attorneys’ fees and interest if Allstate would simply pay the $33,321.80 invoice.

Allstate, through its lawyer, rejected the demand outright, stating that “Allstate believes that overhead and profit is limited…to the repair of a structure.” It appeared that Allstate, as an institution, had adopted a new practice of denying overhead and profit for all contents restoration without investigation. Allstate offered no compromise, despite the fact that the contractor had already agreed to substantial adjustments on other portions of the claim.

Cross filed suit on behalf of the restorer against Allstate for insurance bad faith and breach of the contract of insurance. The suit included a claim for legal expenses and attorneys’ fees pursuant to the law of California, which, like many other states, allows recovery of attorneys’ fees when insurance bad faith is proven. Litigation is expensive, but the ability to recover attorneys’ fees enables policyholders and their assignees to seek justice. The right to attorneys’ fees is assignable in most states.

Among other things, the suit alleged:

- Bad Faith. Allstate’s handling of the claim was incomplete and objectively unreasonable. It failed to diligently pursue a thorough, fair and objective investigation and failed to pay benefits rightly due under the Policy. It failed to fully or properly explain or document its coverage decisions.

- Overhead and Profit. Allstate foreclosed any possibility that overhead and profit could ever be considered for mitigation or contents. Allstate is obligated to judge each claim on its merits and unless an exclusion applies, it must pay the costs reasonably incurred to address the unique circumstances of each loss. By falsely claiming it does not cover overhead and profit for mitigation and contents, it misrepresented the terms of the Policy, in violation of Insurance Code section 790.03.

- Splintering. This six figure loss was complex and it involved the management of a large number of trades by the contractor, including, without limitation, electrical, flooring, cabinetry, drywall, painting, demolition, and contents. Hence, the project required extensive coordination, oversight and financing. In an effort to avoid paying overhead and profit for the contractor’s work on personal property (contents), Allstate engaged in the bad faith tactic of “splintering” the project into small pieces in order to minimize the significance of the pieces, while ignoring the magnitude of the project as a whole. Allstate ignored the fact that the contractor had to coordinate and sequence this work amidst at least seven other trades.

Cross designated claims expert Jeffrey Taxier as an expert witness for trial. Mr. Taxier had worked in the Allstate Claims Department for 35 years. He began as a property claims adjuster and worked his way up to the role of Property Claims Manager of Allstate’s Southern California Claims Department, a position he held for seven years. He then moved to Allstate’s Home Office where he was primarily responsible for the training of Allstate’s property adjusters. After he retired from Allstate, he worked as the Education and Training Manager for ATI Restoration for eight years.

Mr. Taxier prepared a report which stated that a reasonable markup should be paid on portions of restoration work that are managed and/or coordinated by the contractor, regardless of who does the work, and should not be denied unless:

- The basis for the markup has been thoroughly investigated on a case-by-case basis; and

- The results of the investigation are well documented; and

- The decision to deny payment of the markup flows logically from the documentary evidence, careful application of the controlling law, and the governing policy provisions; and

- The bases for the denial are thoroughly explained in writing to the policyholder or the policyholder’s assignee.

The report also states that with rare exceptions, the magnitude of a loss may influence the level of complexity. It also points out that Xactware (for example) does not publish research about overhead and profit, nor does it recommend ten percent or any other percentage, and that contractors in a competitive market may elect to charge more than ten percent. It quotes the Xactware White Paper which states that the amount of overhead and profit, as well as how and where it is accounted for within the estimate is left to the discretion of the estimator based on the conditions of the job.

Adjusters sometimes refuse to pay overhead and profit for contents because they do not consider it to be a construction trade. However, the coordination of the contents portion of a project can be a complex and time-consuming process, particularly in a larger residence with a large volume of contents.

Allstate took Mr. Taxier’s deposition in the Aliso Viejo case. Taxier testified that he does not look at contents in isolation for purposes of deciding whether to pay overhead and profit. Instead, he believes contents should be treated like any other construction trade.

Taxier also testified that:

- The decision to pay overhead and profit is not necessarily dependent on the level of coordination performed by the general contractor. Other factors may warrant payment of overhead and profit.

- Complexity of a project is a factor that should be taken into account by an insurance company in deciding whether to pay overhead and profit, but “complexity” is not necessarily determined by the number of trades needed to complete the project.

- Complexity is determined by the type of work, the amount of time it takes to perform the work, the degree of difficulty of the work, the difficulty of access to jobsite, the risk assumed by a general contractor when subcontracting parts of the project, and many other potential factors.

He testified that Allstate paid overhead and profit on the vast majority of the fire losses he managed during his 35-year tenure with the insurer. He testified that Allstate acted in bad faith by refusing to pay the overhead and profit to the contractor for the contents work on the Aliso Viejo claim.

Settlement

The lawsuit asserted a claim for the $33,321.80, plus interest and attorneys’ fees. Without admitting liability, Allstate paid $335,000.00 to settle the dispute before trial.

Do You Have Evidence to Support Your Price and Billing Method?

The restoration contractor was empowered by a detailed report that listed hundreds of claims in which the restorer had been repeatedly paid overhead and profit for mitigation and/or contents by dozens major insurance companies. This was powerful evidence of the reasonableness of overhead and profit for mitigation and contents.

Each accounts receivable record should include the name of each insurance company and the amount it paid. The more often a restorer is paid a certain price or a certain category of charges such as overhead and profit, the easier it will be to make the case that those charges are reasonable and should be paid by insurance in the future. Track the payment history!

Parting Thoughts

The contractor in the Aliso Viejo case complained about a history of inconsistency in Allstate’s handling of overhead and profit. It urged Allstate to add clarity to its claims handling guidelines and practices. Restorers should be able to find some reasonable degree of predictability about what carriers will pay. This is an important factor to help restorers decide which projects to accept. Unfortunately, unnecessary friction between the restoration and insurance industries will continue and policyholders will suffer as long as carriers decide big ticket items like overhead and profit using amorphous and vague theories that are not based on policy language. The policy controls.

Ed Cross, “The Restoration Lawyer,” represents restoration contractors from offices in California, Hawaii, and Texas. His firm drafts restoration contracts, collects money for restorers, and represents them in litigation, including insurance bad faith. He is the principal of the Restoration CrossCheck LLC, a consulting firm for restorers. He can be reached at (760) 773-4002 or by email at [email protected]. For more information, please visit TheRestorationLawyer.com and RestorationCrossCheck.com.

Disclaimer: This article is general information and is not intended to be legal advice. Settlements are compromises that are not binding on other courts.

[1] 10 CCR § 2695.4(b).

Read more here https://candrmagazine.com/allstate-pays-contractor-335000-to-settle-dispute-over-33000-restoration-invoice/

Get EMPOWERED with an Assignment of Insurance Rights https://edcross.com/aob/